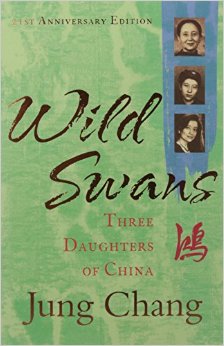

China has always been a source of fascination for me. The aesthetics of the architecture, the calligraphy, the dramatic and beautiful landscapes, and the violent history, filled with martial arts, fantastic heroes, and political intrigue. But, I won’t lie, my interest was focused on the mythological past, the stories told in wuxia cinema about China in it’s prime, when it was a world leader in technology and culture. So reading a book about the modern history of China, focusing on the 19th Century, would not normally have been my first choice. But it was recommended to me, and I have an interest in socialist politics, and I’m always trying to expand my horizons. And I am happy to say that I’m glad I read this book. It is not a short book, hardly surprising bearing in mind the scope and depth it covers. But I was transfixed by the story throughout, from cover to cover.

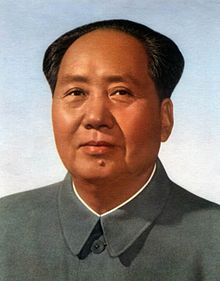

The author, Jung Chang, retells the story of herself, her mother and her grandmother, from the early 1900s to the 1970s, a few years after the death of the main (though abstracted) antagonist in the book, Chairman Mao. By keeping the story centered around her own and her families experiences, she ensures that the personal story never gets too bogged down in the complicated politics and harrowing events that her family lived through. Because of this grass-roots perspective, this is not a book that details the overarching political machinations of the age, although these are touched upon in order to give context to the very human story that is told here.

This, perhaps, is a criticism of the book, as sometimes the personal details are put at the expense of the historical context. But it is a minor one, as the book is unashamedly a human tale, and this keeps the story of such a huge country with a complex society and history accessible. The human side of the story is a tale of much suffering, hardship and disaster. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the knowledge that Chang eventually escaped her circumstances following the downfall of Mao, it would be an overly tragic tale. For much of the book there is little relief from the misfortunes that beset her family, particularly her parents. But in this respect, it seems to be a good description of the oppression and senseless violence that were hallmarks of Mao’s rule.

There is a good cast of supporting characters, both villainous and altruistic. But we are never allowed close enough to them for the story to fall aside from its purpose of telling a modern history of China through the eyes of three remarkable women. The story finishes in the late 1970s, when Chang moves to Britain. But I found myself desperate to find out about how China has changed in the last 30 years.

In conclusion then, this is an exciting and interesting human story, which gives a good overview of China in the 19th Century, but more importantly how the complex politics of the time impacted ordinary people trying to live their lives.