‘In converting a passion into a set of facts, [one is] at least following a pattern with an established pedigree, most notable in academia, where an art historian, on being stirred to tears by the tenderness and serenity he detects in a work by a fourteenth-century Florentine painter, may end up writing a monograph, as irreproachable as it is bloodless, on the history of paint manufacture in the age of Giotto. It seems easier to respond to our enthusiasms by trading in facts than by investigating the more naïve question of how and why we have been moved.’

Alain de Botton in The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work

“It seems easier to respond to our enthusiasms by trading in facts than by investigating the more naïve question of how and why we have been moved”. When I first read this I was struck by its profoundness, and its pertinence to me as I approach the cliff edge of finishing my MSc and begin thinking about spreading my wings and entering the job market, as opposed to instinctively curling into a ball and hoping that my death on the rocks below will be quick and painless. This has led me to inevitable questions about why I decided to continue my education in the first place (probably ones I should have asked myself when at the start of the course, rather than now!)

When I talk about it, most people want to know if having a master’s will increase my employability, because of course the most important reason to get an education is to furnish you with the skills and knowledge necessary for a career. The truth is it probably will help me get a ‘proper job’, as the environmental employment market is awash with graduates and a master’s at least puts you into a slightly smaller pool. But that’s not really why I decided to go back.

I don’t think I’m under the illusion any more that I will ever be finished with learning, and whilst I appreciate that learning is possible in a work-environment, I can’t help but feel that unless it is a primary concern of an employer, learning will never be the focus of a job. So it made sense to go to a place that prioritises the accumulation and creation of new knowledge as its primary purpose – the university. But why the need to learn so much? This may sound conceited, but maybe it’s because I take a lot of pleasure in knowing things, especially if they’re things that other people don’t know. But perhaps, as de Botton says, my desire to study the natural world scientifically, reducing it to facts, figures, statistics and scientific journals, is just a way to avoid questioning how and why the natural world moves me.

It’s certainly true that the reason I love wildlife is not because I read a treatise on the genetic history of Falkirk’s Shrew, or because I found that the population increase of a controlled population of spiders is 1.8. My love comes from childhood nostalgia of walking through woods, along rivers and up mountains. It’s from the amazing sense of raising a family of butterflies from egg through caterpillar and pupa, to glorious adulthood and watching them fly free, gliding out of my open window into the incomprehensible vastness of the outdoors. It’s from reading the delectable descriptions of Corfu by Gerald Durrell, and hearing the dulcet tones of Attenborough and Oddie on my television. It’s even from immersing myself in the legendariums of Tolkien and Pokémon, where a connection to nature is embedded in the very fabric of those worlds.

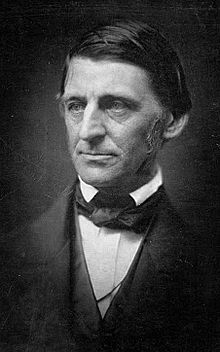

Ralph Waldo Emerson says, in his essay Nature, that it is humanity’s perception of a connectedness to nature and the universe that draws men to science:

‘but the end is lost sight of in attention to the means. In view of this half-sight of science, we accept the sentence of Plato, that “poetry comes nearer to vital truth than history.”’

Maybe it is too much of a leap to draw together job-hunting and the search for ‘vital truth’ in just a couple of paragraphs. But when working in a field that rewards you in job satisfaction, rather than materially, an understanding of why you do what you do is vital. So I hope that, in whatever role I end up in, I can continue investigating not just the facts, figures, tools and techniques of the job, but the more naïve question of how and why I have been moved.