Despite the universe trying to remind me daily that my expectations are always further from the truth than I imagine, I can’t stop finding myself continually struck by how wrong my initial judgments of things are. This book is a perfect case in point. I bought it for the following reasons: it was in the travel section; I like snow leopards; the cover was unbelievably beautiful. If you’re now asking if I literally judged this book by its cover, you’re correct. Whilst I acknowledge that this is practically heresy, I’m actually going to defend my actions here.

The reason one should judge a book by its cover is the same reason that, if someone offers or recommends a book to you, you should read it. Simply put, it encourages broader horizons, and perhaps the opportunity to try a book you haven’t tried before. My experience with The Snow Leopard was revelatory, but had I known more about it when I started, there’s a good chance I would have missed out completely.

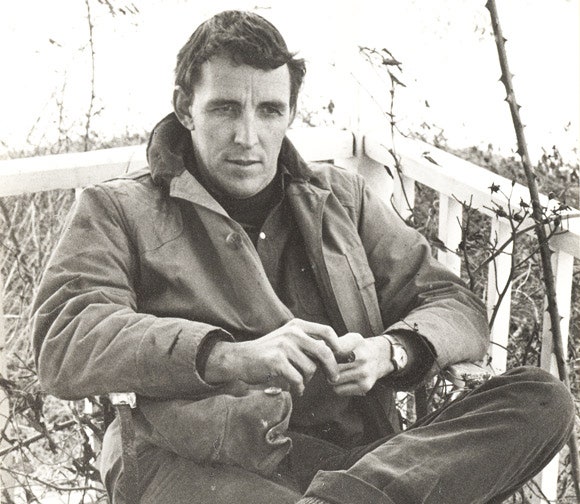

The book covers Peter Mathiessen’s expedition into the Nepali Himalayas, accompanying the scientist George Schaller in his research around the habits of the Bharal, or Blue Sheep, that inhabit the area. Over the course of that journey they are joined by or encounter various Sherpas, porters and villagers who inhabit the inhospitable and harsh mountain environment. Mathiessen is also a practicing Buddhist, and his trip doubles as a pilgrimage to the holy temple of Shey Gompa, underneath the Crystal Mountain, where he meets and engages with a holy Lama (as in ‘Dalai’ not ‘here’s a, there’s a, and another little etc.). But the book is not really a travel book, nor an adventure book, nor a scientific account of the breeding habits of Bharal, although it has elements of all of the above. The author had, a short while before the start of the expedition, lost his wife to cancer, and really the book is more about his spiritual journey dealing with her death, reaffirming his faith, and attempting to find his pace and place in the world.

I came to this book expecting an adventure story, which it’s not, featuring snow leopards, which it doesn’t, and as this became apparent whilst reading the book, I quickly began to find reading it a struggle. The lack of fulfilment of my expectations, coupled with the overuse of Nepali names, Buddhist terms and pretentious prose (including a good deal of what initially struck me as spiritual waffle) almost caused me to put down the book and never pick it up again, such was my frustration and indeed boredom at certain points. But at a certain juncture I began to forget about what I wanted the book to be, and just accepted that this was what it was. And when I changed my perspective, adjusting to its style and pace, I realized that the prose, although in some cases pretentious, was actually very beautiful and evocative. The muddle of names of characters and places no longer bothered me. Who was saying what or where they were wasn’t important to the story, as Mathiessen’s internal journey was only affected by how he perceived what was happening, and not with whom or where. The story is insulated and introvert, with the drama coming from the author’s observations about the self, the mind and body, and the ever-evasive spirit. Indeed the humans we are introduced to are not really the supporting characters of the book, as they are overshadowed by the immensity, power and changing nature of the landscape, the mountains which seem to act as inspiration for the author’s gradual acceptance of the way things are, something he attempts to achieve from the start of the book. But it is only within the solitude of the mountains, his removal from all aspects of modern life, that Mathiessen is able to match his feelings, behavior and outlook to his aspirations.

One of the things I enjoyed most was the way a small detail in the physical landscape, the shade of a river or the light on the snow, can be examined and extrapolated into questions about the human condition, or life and death, or any number of other philosophical topics. Yet these deep and lofty questions never threaten to overwhelm the book, as they are mere musings of a man half-way up a mountain, wet, cold and breathless, but liberated and free from any sense of self-importance, and unworried by the consequences or answers to the questions he ponders: “the secret of the mountains is that the mountains simply exist, as I do myself: the mountains exist simply, which I do not. The mountains have no ‘meaning’, they are meaning.”

This is not an easy book to read. It requires effort, investment and a certain amount of just accepting that this is the way the book is. But it is also immensely rewarding, interesting, and quite beautiful. Without wanting to labour an analogy too much, I feel in many ways that as you accompany Matthiessen on his spiritual journey, you go on one yourself. There are difficult points when you don’t wish to continue, but as you get deeper into the mountains you learn acceptance, and this brings serenity. As Matthiessen journeys away from the mountains at the end of the book, and back into the lowlands, the peace and certainty he discovered there begins to vanish. Similarly I began wishing the book was longer, so that the prose and insights I had become attached to didn’t have to end, forgetting as he does to accept the reality we are presented with. But really this just emphasizes the success of the writing. The book does something that I don’t believe to be that common. Rather than telling you the story, and asking you to follow it through your imagination, this book allows you to come along, experiencing and feeling the same emotions that the author himself did. And I think that is a good mark of a book. Did you enjoy the story? Yes, but not as much as I relished the journey.